Your essential guide to making OKRs actually work for your organization

From strategic alignment to motivating teams, here's how to get it right.

By Neel Doshi & Lindsay McGregor

"If you promote me, I'll quit." That's what a high-performing Google product manager told his boss.

Why? He watched the leaders above him spend most of their time "negotiating" OKRs. Not building, not solving, not leading—just wrangling over goals. He wanted no part of it.

Why do our OKRs feel like a chore and not a driver of performance?

There are plenty of examples of good OKRs, and plenty more examples of bad OKRs. If you want to avoid your organization descending into a demotivating, bureaucratic mess, you need to understand the difference.

Good OKRs versus bad OKRs

Two teams walk into a room. One is going to win and the other will lose.

They have three hours to build a model of a “smart pedestrian bridge”: something safe, functional, and sturdy enough to represent real-world use. There’s no right answer. Just a clock ticking and a table full of cardboard, tape, and ambition. Same materials. Same time limit. Same challenge.

Three hours later, the difference is impossible to ignore. One team’s bridge is shaky. It only stands if someone holds it upright. Corners sag. The team insists they followed the plan. They hit their milestones. They did what they said they would do. The other team’s bridge stands on its own. It includes a number of smart design choices along the way. So why did one team win and the other lose?

The first team used OKRs the way most companies do. They set OKRs upfront, broke the work into pieces, assigned responsibilities, and then executed. There was no revisiting assumptions, no changing direction. Progress meant sticking to the plan, even when things started to wobble. The second team used OKRs the right way. They treated objectives as problems to solve and hypotheses, not commitments. They paused regularly to ask whether what they were building was actually working, reallocated effort, and changed their approach midstream. Their key results weren’t scorecards—they were signals. And when the signals said something was off, they adapted.

This controlled experiment, conducted at Bangkok University, clearly shows the difference between good and bad OKR models:

OKRs, when executed properly, can be incredibly effective. OKRs executed poorly can become a bureaucratic distraction.

What went wrong with OKRs, and why aren't they working as promised?

Why is it so common for good ideas to become the worst versions of themselves? This is the law of conceptual decay.

This law says that when organizations (and consultants) try to scale good ideas, they overemphasize the tactical (process, pressure) and underemphasize the adaptive (skill, motivation).

Process and skill are opposites. For example, I can follow a recipe and make a good meal. But if anything isn't exactly as specified, I wouldn't be able to taste my cooking as I go and adapt. That's where skill comes in. And proper mastery of any skill requires understanding the first principles of that skill.

When many organizations scaled Agile and OKRs, they often aimed to replace skill with more process. But seldom does this trade pay off. Instead, good concepts become bureaucracy. The irony with Agile is that it became the exact opposite of its manifesto:

The Agile Manifesto.

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

OKRs have gone down a similar path and as a result, bad OKRs significantly outweigh the good OKRs.

To get back to good OKRs, we need to make sure all leaders know the first principles. The babies, so to speak, from the bathwater.

Are you confusing OKRs for KPIs?

Think of good OKRs as your car's or phone's navigation system.

- Your vision = the destination you plug into the navigation system.

- The OKRs are waypoints or milestones along the way. Like points where you may need to make a turn or stop to recharge.

On the other hand, KPIs are like the gauges on your dashboard, like your speedometer or fuel indicator. They make sure the machine is working the way it needs to.

The BAU work of an organization is (often) best managed through KPIs. For example, a healthy sales funnel requires 100 calls per day. Or a high-quality customer support experience requires 24-hour resolution times. A performant microservice may have 99.9% uptime. These all should be managed via KPIs.

Bad OKRs are often KPIs in disguise.

OKRs, on the other hand, are best for growth (not BAU). This is the work needed to drive change or create something new.

If you lead a team or organization that has BAU work and growth work, you should have two aspects to your management operating system (and make sure you don't cross the streams).

- The tactical BAU portion that is driven with KPIs.

- The growth opportunity portion that is driven with OKRs.

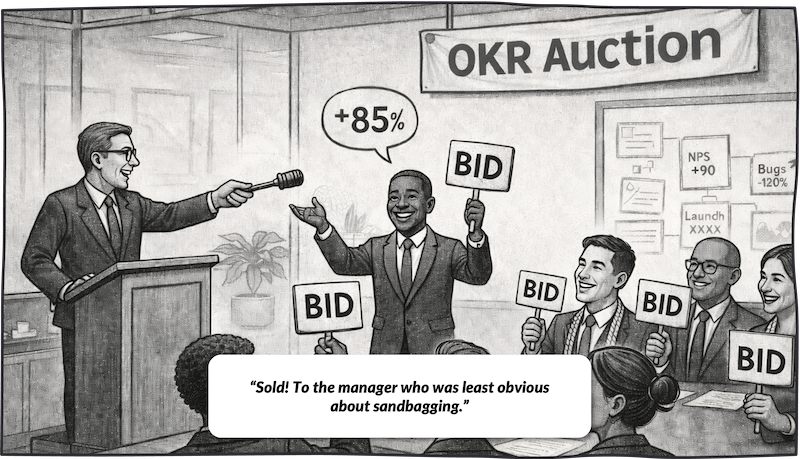

A good OKR system should make it easy to name the problems you have to solve, and easily see if you're making bandwidth to solve those problems.

The example above from the Factor.ai platform shows you what a team's OKRs should look like.

Why strategy, not targets, drives true growth

Imagine you are a star college football player. You end up going to your dream Division 1 college. On the first day, the head coach says, "Okay guys, your goal is to win 85% of your games. I'll see you at the end of the season for your performance reviews." How do you think that player is going to feel about his coach?

When companies implement bad OKRs (by conflating KPIs with OKRs), it often feels like you're playing with this lousy coach.

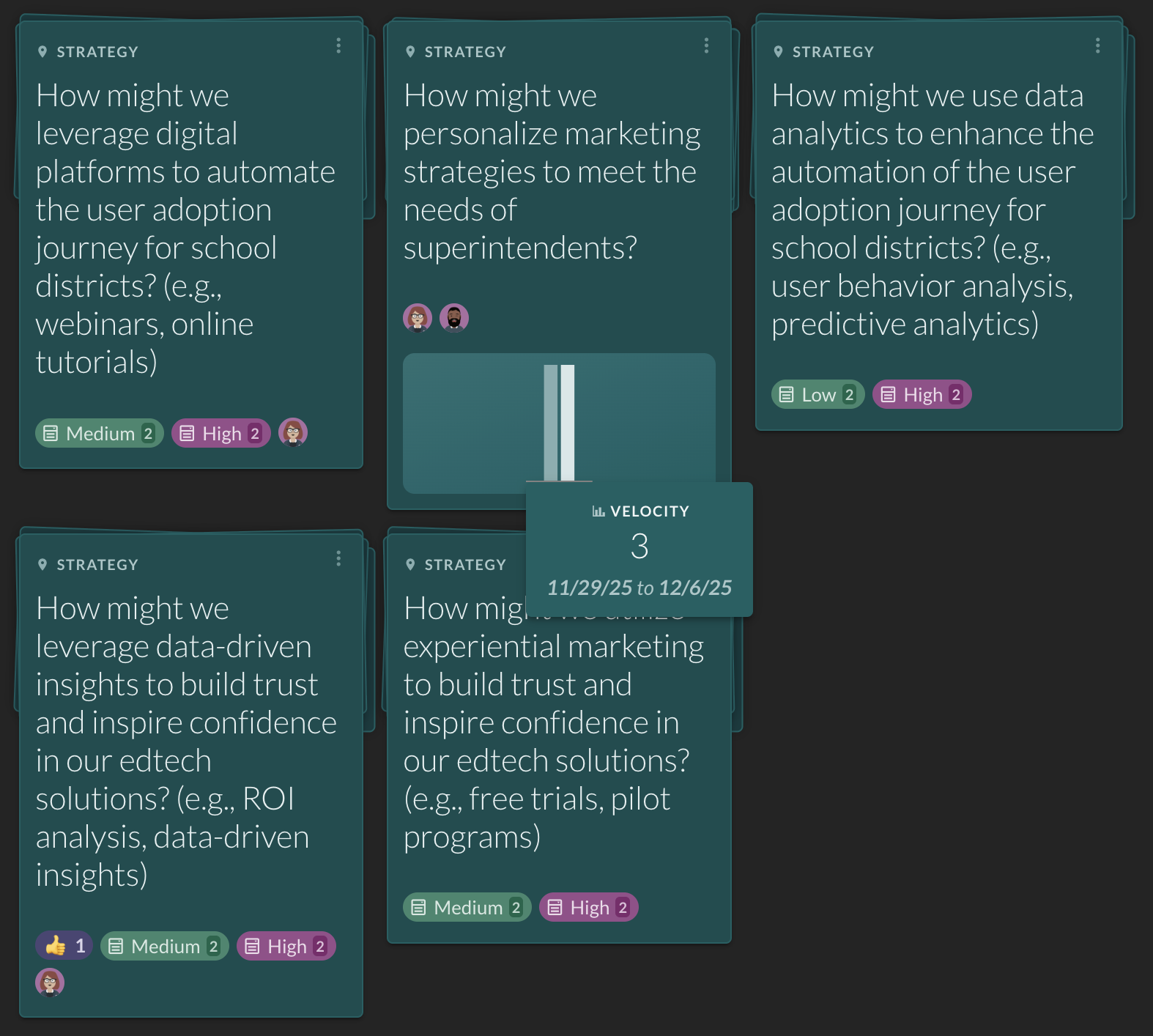

Instead, OKRs, as they cascade down an organization, should result in the tree of problems an organization is solving right now to head towards its vision.

For example, the Strategy analytics view in Factor.ai shows this tree of OKRs along with a view on what's blocking them, recent decisions, and progress made.

We recommend that an organization's management operating system require:

- An annual vision-setting session

- Strategy Checks to build good OKRs every three to four months. The Factor.ai platform uses AI to ensure these are good, not bad, OKRs.

- Weekly written reflections for all OKRs from their owners. The Factor.ai platform uses AI to interview all the OKR owners to make sure they are reflecting about the problem, not just their tasks.

Breaking down walls: how OKRs can foster collaboration, not create silos

Conway's Law is an observation that organizations tend to solve problems in ways that reflect their organizational structures.

For a long time, Uber's separate organizational structures for its Mobility (ride-sharing) and Delivery (Uber Eats, etc.) apps often resulted in a disjointed user experience, where the two services didn't communicate seamlessly, treating users almost as separate entities. This direct reflection of Conway's Law, where internal communication structures manifest in product design, prompted a significant leadership reorganization in 2025 to unify these divisions under a single COO. The strategic goal was to intentionally rewrite their software architecture and create a more cohesive platform experience, demonstrating how a deliberate change in organizational structure can lead to a more integrated and user-friendly product.

Often, in the world of bad OKRs, companies start with their org structure and have different functions and teams make goals. But this approach (which works for KPIs) results in siloed thinking that slows down growth and innovation.

Instead, when organizations cascade their strategies via Strategy Checks, they should focus on how to break down those problems first.

Ultimately, large organizations will have three different organizational structures:

- The strategy structure: This is the tree of how the vision breaks down into problems to solve across the organization. This structure is based on the right way to solve these problems, not limited by the reporting line structure.

- The reporting line structure: This is the structure of who reports to whom—what organizations typically think about when they say "structure."

- The team structure: Increasingly, organizations are realizing that strategies often require cross-functional teams. So, they are creating team structures that sit somewhere between the strategy and reporting line structures.

Measuring what matters: escaping the lamppost effect in goal setting

There's that old story about someone looking for their lost keys under a streetlamp, not because that's where they dropped them, but because that's where the light is.

This story illustrates another way good OKRs turn bad. Rather than focusing on the right problems to solve, the problems themselves are limited by what is easily measured in the key results.

The fix here is rather simple. Start with getting the problems and hypotheses right. This doesn't mean you need to have every problem solved. It only means that you need to name the problem.

And then, based on the problem and hypothesis, find the easiest, cheapest ways to "measure" the resulting "inputs" and "outcomes."

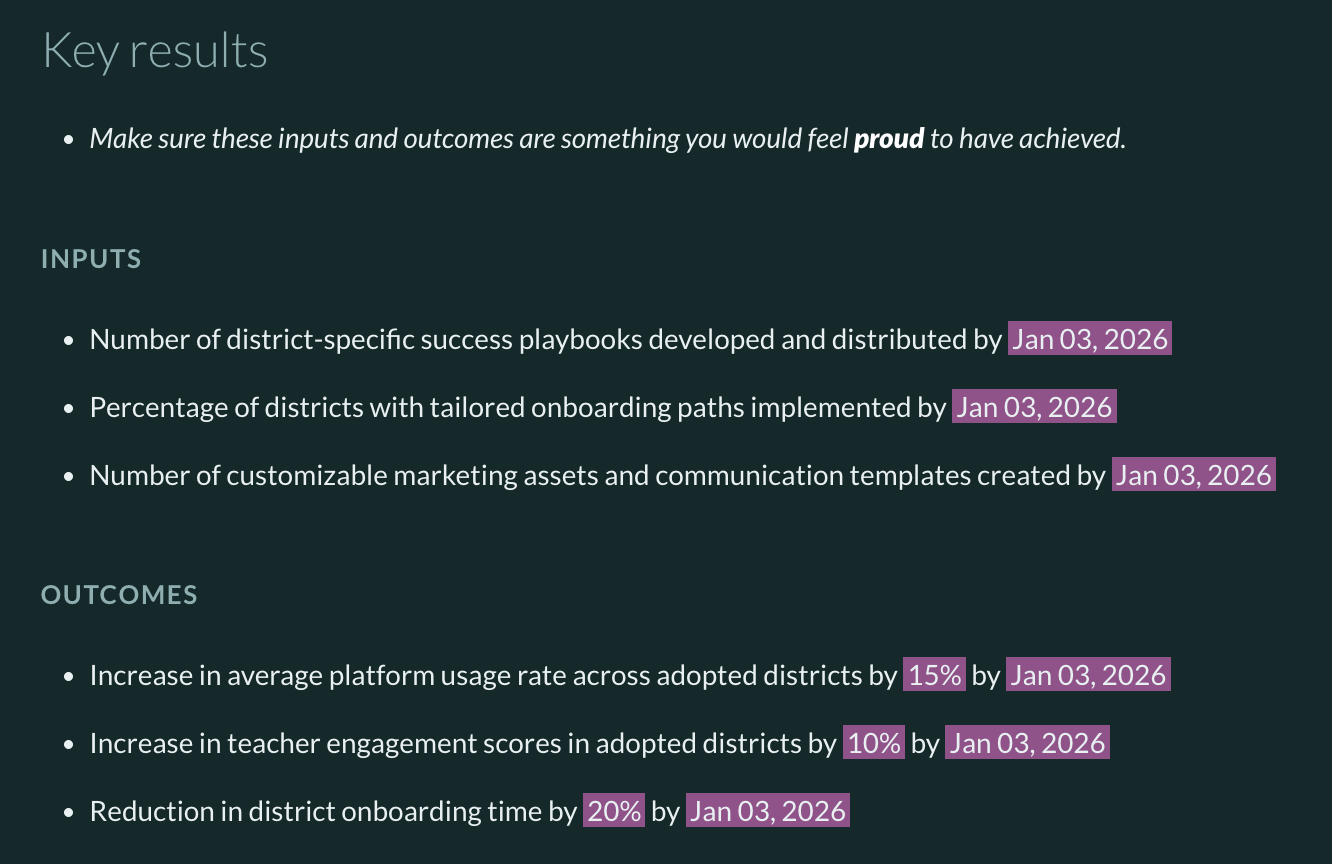

As an example, when teams create their OKRs in the Factor.ai platform, AI helps them come up with ways to measure the inputs and outcomes. They can then choose the cheapest and easiest measures.

Making OKRs a source of motivation, not bureaucracy

If OKRs are a "negotiation" process, as mentioned by the Google leader earlier, it's a telltale sign of bad OKRs.

Instead, OKRs should be part of how groups of people solve problems together. One of the most important first steps when groups of people have to solve problems is that they agree on the problem being solved. That's the core of good OKRs.

Good OKRs not only help make sure we all are solving the same problem together, but we also have similar expectations. For example, when the Factor.ai platform helps people set OKRs, it has them answer five questions to make sure we're all playing the same game:

- Does this problem require discovery or do we already feel confident in a solution?

- Are we aiming for innovative (thus higher risk and reward) or iterative (thus lower risk and reward) solutions?

- Will solving this problem require changing people's mindsets and behaviors (and thus higher risk and longer time frames)?

- Should we check in with our stakeholders often or just move as fast as possible without checking in?

- When do we expect to see the impact of this problem being solved?

By making the process more about a group of smart people solving the same problem, it increases your people's sense of play, purpose, and potential.

Your path forward: building an OKR system that actually works

It's clear that the OKR framework itself isn't the enemy; it's how we've distorted it. We've seen how a powerful idea, meant to drive growth and motivation, can become a bureaucratic chore. But you don't have to abandon OKRs entirely. The good news is, you can reclaim their power.

To transform OKRs from a performance killer into a performance motivator, leaders need to make a conscious shift. You need to distinguish OKRs for growth from KPIs for business-as-usual. Prioritize strategic problem-solving over mere goal-setting, because true leadership designs, not delegates, strategy.

Foster cross-functional collaboration by building strategy structures that cut across reporting lines. Measure what truly matters, even if it means getting creative. And above all, design a process that inspires and motivates your teams, not one that drains them.

The goal isn't to throw out OKRs, but to reclaim their original intent and power. When you do, you'll find that OKRs can be a source of energy, alignment, and real progress—not just another box to check.

Further reading

- How company culture shapes employee motivation: Explore how culture drives motivation and performance, and how to build a high-performing environment.

- Is everyone fit to lead?: Learn why leadership is critical for team performance and how to develop leaders at scale.

- Three ways to build a culture that lets high performers thrive: Discover strategies to nurture high performers and create a culture that attracts and retains top talent.

- Why do most strategic goals fail?: Understand the common pitfalls in goal setting and how to align strategy with execution.

- The problem with performance management - and how to fix it: Find out how to balance tactical and adaptive performance and create effective feedback loops.