How excuse-making derails transformational change and leads to the death of companies

It isn't just you. Leading in the last five years has been an absurdly wild ride.

Covid. Remote work. Gen Z work preferences. Supply chain bullwhip effect. Political volatility. Trade wars. The rise of TikTok. The power and hype of AI. And all of this in only the last five years.

Just the last five years!!!

Now ask yourself, how many of these changes did your company predict in its strategy five years ago? None.

Welcome to the era of permanent change.

In this era, adaptability is the most important capability. So why, then, do so many organizations struggle with change?

Research consistently shows that only 3 out of 10 corporate transformations succeed. Why?

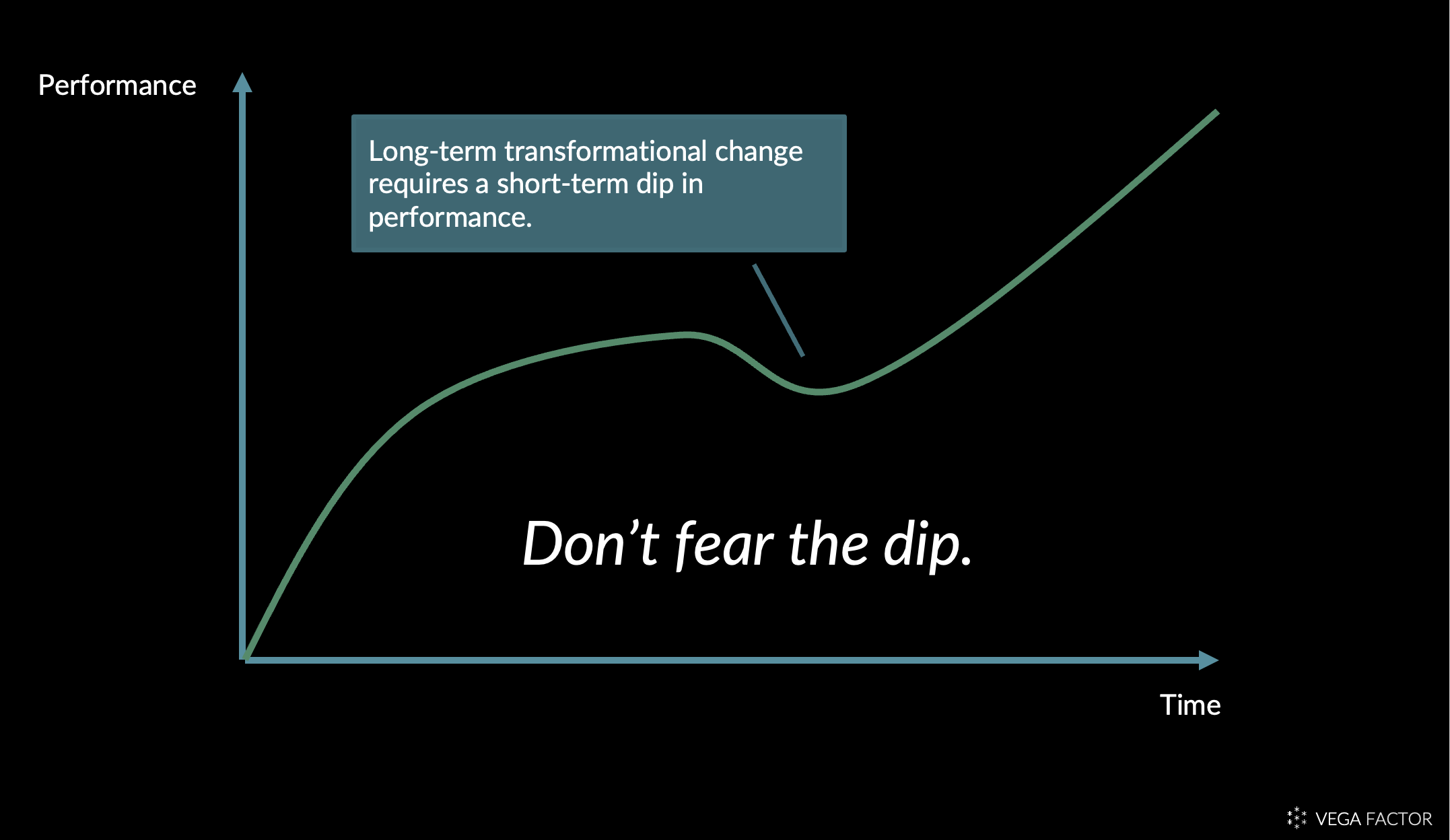

There's one major insight that explains why so many leaders struggle to drive transformational change in their organizations. They don't realize that transformational change means performance will get worse before it gets better. And their organizations don't tolerate the dip.

What is transformational change, and why is it so hard to get right?

Greatness is never set-it-and-forget it.

Consider a contender for GOAT of GOATs: Roger Federer. By 2016, at an age when most players are retiring, he chose a different path.

The physicality of the modern game, dominated by younger, more athletic players, proved to be too much for his aging body. Instead of going gentle into that good night, he changed his game.

For the year, he fundamentally overhauled his gameplay—a style that others would have considered perfect.

To conserve energy and shorten points, he reinvented his backhand, stepping further into the court and taking the ball earlier to hit flatter, more powerful shots. He also increased his net approaches to finish points more quickly. This was a deliberate shift: less grinding from the baseline, more attacking, more risk, and more pressure on his opponents to end rallies fast.

This kind of change couldn't be done without a temporary dip, and while he was making it, his performance suffered. His rank slid to 16 in the world, and many considered his best days over.

Federer understood that there are two types of change.

First, there's incremental change—these are changes where performance improves immediately. For example, simple process changes in companies can improve performance right away.

Second, there's transformational change.

A typical large language model's definition for transformational change is: "a profound, radical shift that fundamentally alters the core of an organization, often in response to or anticipation of major changes in its environment or technology."

But for leaders, the most critical thing to understand is this: transformational change is when performance will worsen before it gets better again. And that's exactly why these changes are so difficult to lead.

Why do companies fear the dip and thus fail at change?

Transformational change requires companies to endure a dip in performance as they learn to change their game. But many companies fear the dip.

That fear isn't simple to fix. It's built into the bones of the organization. To lead through this challenging aspect of change, it's important for leaders to understand how fear gets codified into their very systems and structures:

- Mistaking niceness or cruelty for motivation

- Using pressure to drive BAU (and thus preventing growth)

- Seeking buy-in rather than seeking action

- Using BAU feedback loops to drive transformational change

Can we be nice and high performing?

Too many companies have so over-indexed to "psychological safety" that they've made their companies less motivating.

Before the sour comments pour in, are there still toxic leaders? Yes. Should they be toxic? No.

But under the flawed flag of psychological safety, too many companies have replaced motivation for sterile, nice, conflict-avoidant companies.

To understand how to thread the needle between a safe culture and a challenging culture, leaders must understand the first principles of how motivation works.

I'm going to compress the book, Primed to Perform, into two paragraphs, but if you lead humans at work, read the whole book.

There are fundamentally six motives (reasons why we do things). These motives are the roots of motivation:

First, the motives that come from challenge:

- Play: you do something because it is fun. But it is fun because it is challenging or novel in some way.

- Purpose: you do something because your contribution matters.

- Potential: you do something because it will lead to something meaningful to you.

The best performance coaches, like the ones who build the best high-performing teams, use these motives as their primary form of motivation.

The application of these motives doesn't always feel "nice." Challenge sometimes comes from tough love, conflict, or hand holding.

On the other hand, there are three motives that come from coercion or apathy:

- Emotional pressure: like fear of judgment

- Economic pressure: like the pursuit of rewards or avoidance of punishment

- Inertia: no reason for action

These three motives may instigate an action, but do not result in sustained, adaptive performance.

When leaders are "nice" and thus conflict averse, they are unlikely to be motivating. Often this feels like inertia—even the leader doesn't seem motivated to perform. These leaders will not successfully navigate their organizations through the dip.

How can we create growth mindset in our organization?

In at-scale organizations, there are two types of work:

- BAU (business as usual): BAU work is about keeping the lights on, defending your share, and maintaining momentum. It's all about keeping the company on its current course.

- Growth: Growth is new efforts. Zero-to-one initiatives. Growth is about creating a new course.

Transformational change falls into the Growth category, but most organizations have management systems fixated on BAU.

- All the metrics: BAU.

- Compensation: BAU.

- Management routines: BAU.

- Goals: BAU.

BAU work has all the motivation and pressure, so BAU work doesn't just fill your calendar; it dominates it.

The most common rhetorical tactic used by leaders in these systems is the false choice. It sounds a bit like this: "Well, I can either close the deal with that client or participate in this transformation."

Instead, executives have to be prepared to say, "I understand this won't be easy, but we must figure out a way to do both, and figure it out together. We're in the era of permanent change. Winning today and losing tomorrow isn't any better than losing today and winning tomorrow."

How can I create buy-in for difficult change?

In the late 90s, I pitched a transformational strategy for the internet to the then CEO of Citi, John Reed. I was 21 at the time (and deeply clueless), so he said I needed an executive sponsor for this idea. He introduced me to a number of executives, to see if I could get buy-in.

One executive flat out told me, "I agree with your idea completely, but I'm not going to support it. I'm two years from retirement, and I'm not going to stick my neck out for anything new."

The problem with seeking "buy-in" for transformational change is that there are too many reasons to not buy-in that have nothing to do with the quality of the idea:

- As you saw above, an executive may not have the same time horizon as the transformation.

- An executive may be unwilling to self-sacrifice. Sometimes a transformational change requires one organization to sacrifice its own productivity or headcount for the betterment of the whole.

- A colleague may be afraid of seeming incompetent during the dip.

- An executive may not understand the change, but won't fully understand it until they start doing it (like riding a bicycle).

The worst case is that rather than openly discussing these reasons, the buy-in process is co-opted for stall tactics. Requests for more information. More trainings. More meetings. More analysis. Strings of perpetual short delays.

Rather than spending all this time aiming for buy-in, instead focus on making the steps of the transformation bite-sized. Momentum makes momentum, so aim to get past the cold-start problem as fast as possible.

How can we measure progress during transformational change?

Imagine you're Roger Federer during his own transformational change. How would you measure results? It couldn't be points or even matches won, because he's getting worse before he gets better.

The challenge of transformational change in companies is that their BAU measurement systems won't work.

Instead, organizations have to do something that is often alien to them. They have to:

- Understand the theory of the case.

- Evaluate actual behaviors versus the specific behaviors required in the theory of case.

- Segment their employees into Innovators, Early adopters, Early majority, Late majority, and Laggards, focusing first on the innovators.

- Take the time to learn how to master the needed behaviors.

If an organization is primarily accustomed to BAU management systems, this will feel uncomfortable to them.

Pulling it all together

We've been focused on a critical implication of transformational changes—that performance gets worse before you get better. There's a reason for that.

Transformational changes typically require adaptability. The people in the change either have to learn new skills (which takes time) or make local adjustments to the recommendation (which also takes time to figure out).

Think about it this way. When driving performance, leaders have to drive tactical and adaptive performance and for each, the why, what, and how.

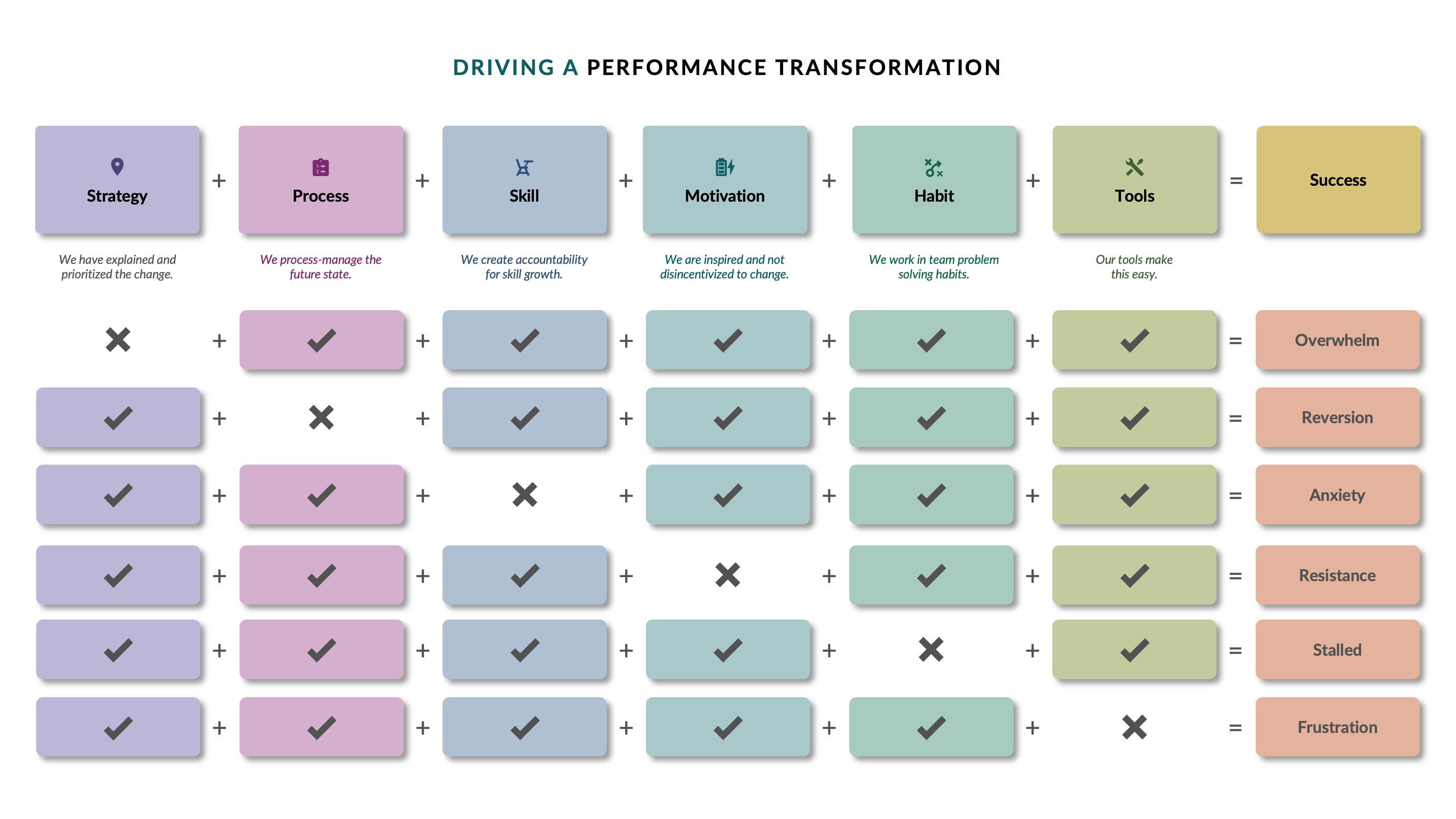

To drive transformational change effectively, you need to make all five of these levers, plus your facilitating tools, work toward the change. Missing any one of them results in common barriers to change.

If you're stuck in a transformation change that is going slower than you want or is trending in the wrong direction, reach out to us. We're happy to spend 20 minutes on a call to see if we can help you get unstuck.

About the authors

Lindsay McGregor

Meet Lindsay McGregor, the best-selling co-author of Primed to Perform, and co-founder of Factor.ai and Vega Factor. She's on a mission to build organizations that are AI Native & People First, because, let's be honest, who wouldn't want a world where every company thrives and everyone genuinely loves their career?

Lindsay is a hard-working nerd at heart. She holds an MBA from Harvard Business School and an undergraduate degree from Princeton University. A former McKinsey & Company consultant, she's also a New York City Library cardholder and a science fiction enthusiast.

Today, Lindsay isn't just talking about change; she's making the tools and doing the science needed to ensure everybody has great professional lives. It's safe to say, she's making work work better for everyone.

Neel Doshi

Meet Neel Doshi, the best-selling co-author of Primed to Perform, and co-founder of Factor.ai and Vega Factor. He's dedicated his career to a pretty ambitious goal: creating a future where all companies are high-performing because they're AI Native & People First. Think of it as making work so good, people actually look forward to Mondays.

Neel looks at this challenge through the eyes of an engineer. He earned his engineering degree from MIT and his MBA from the Wharton School. A former Partner at McKinsey & Company, he's also a Kentucky Colonel and a graduate of the Bronx High School of Science. Neel takes science-nerd to all new heights.

Currently, Neel is focused on showing the world that through science and AI, every team and company can be extremely motivating and high-performing. No one need be left behind in the march of progress.

Further reading

- Should Wells Fargo have fired employees who were simulating keyboard activity? — On remote work, performance culture, and why leadership matters more than surveillance.

- Three ways to build a culture that lets high performers thrive — How to focus your culture on high performers and make new ones.

- Blame is why your culture is low-performing — Why blame hurts performance and how to build supportive accountability.

- There are two types of performance - but most organizations only focus on one — The difference between tactical and adaptive performance, and why both matter.

- How company culture shapes employee motivation — The science behind culture, motivation, and high performance.