Don't implement Cross-Functional Teams before reading this

Is it always better for people to work in teams?

The year is 1882, and you are a foreman on a farm. You have eight strong people working for you, and you need some of them to grab a rope to pull a plow. The rope is long enough that you could have all of them pull it and they have nothing else to do. How many should you assign to the task?

The intuitive answer is to put all of them on it. After all, many hands make light work.

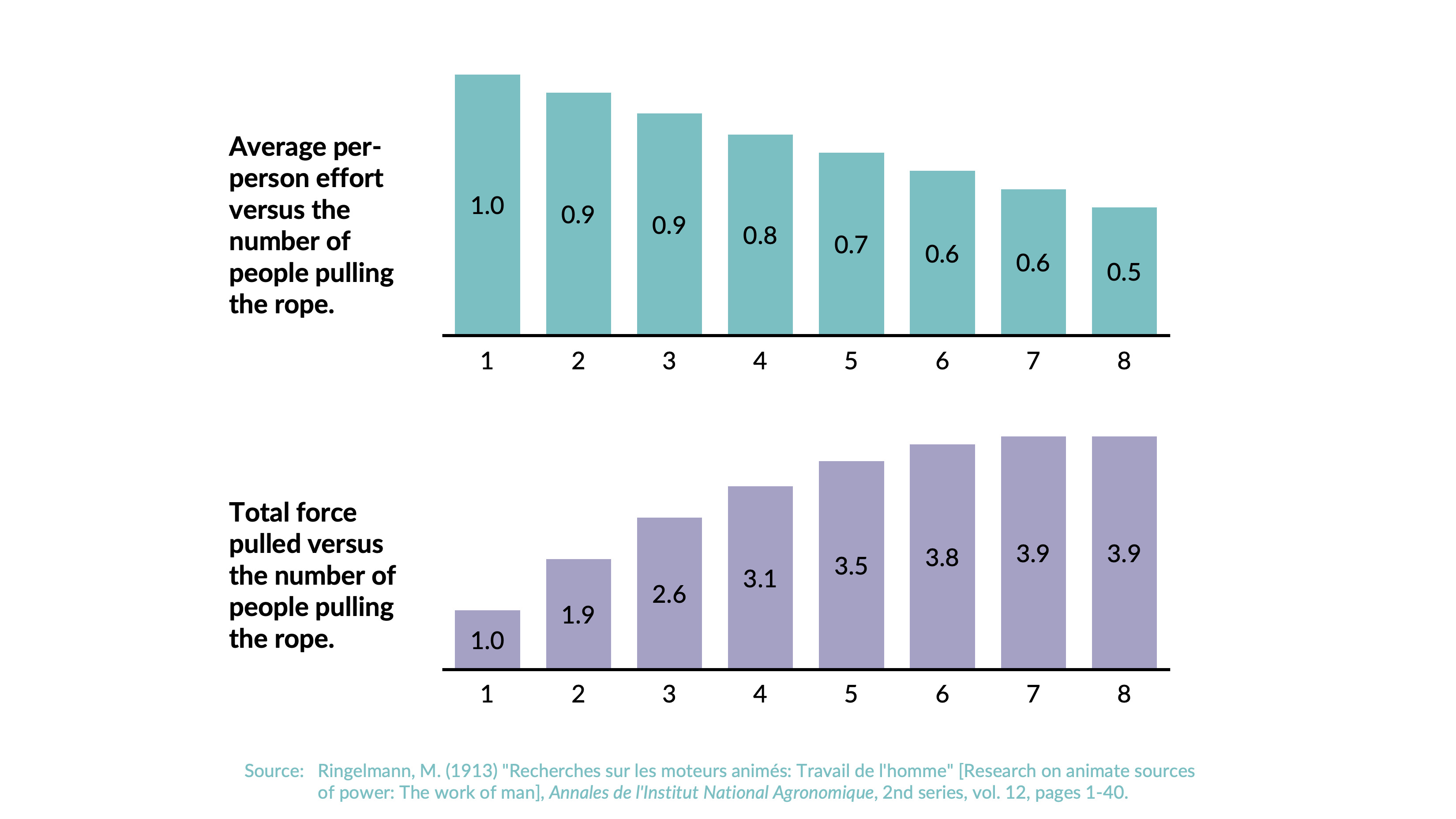

To answer this question, Max Ringelmann, a French agricultural engineer, conducted what many believe was the first recorded social psychology experiment. He carefully measured how much force people exerted when they pulled a rope alone, and when they pulled it with up to thirteen additional people.

His results were mind-boggling. Ringelmann found that when a person was added to the rope, everyone pulled with less strength.

When two people were on the line, they each pulled with 93% of the force of a person working alone. Three people each pulled with 85% of the force, and so on. By the time eight people joined the rope, they were each pulling with half the force of a single person. As a result, a team of eight pulled the rope with no more total force than a team of seven. (Source: excerpt from Primed to Perform).

This drop in performance is driven by a drop in motivation. Each extra person makes everyone else feel more fungible. As a result, they feel a lower sense of purpose and motivation drops.

This and other similar experiments show us something fundamental: simply putting people together in a group doesn't automatically make them more effective. In fact, without the right conditions, you can get diminishing returns, where the collective output is less than the sum of the individual parts.

So, if just teaming up isn't enough, what is?

This is where the idea of Cross Functional Teams (CFTs) (a.k.a., pods, squads, tribes, tiger teams, or mission teams), comes into play.

Companies often reorganize into these structures with the hope of boosting adaptability and thus speed. The core concept is to create small units with all the diverse skills needed to tackle a specific problem or deliver an outcome. It's about creating a structure where the teaming itself is different from traditional hierarchical reporting lines.

Why Cross Functional Teams are a great way to organize

There are many reasons why CFTs are often a higher-performing organizational choice.

Think of a CFT as a mini-business or a strike team. It's made up of people from different functions – like product, engineering, design, and marketing – who have all the skills needed to tackle a specific problem or pursue a particular opportunity from start to finish. The key here is that the teaming is designed to be different from formal reporting lines. People might report to functional managers elsewhere in the organization, but their day-to-day work, their goals, and their accountability are centered within the CFT.

Why is this structure often more effective?

- Motivation through play and purpose: Because the team has greater end-to-end ownership, it is easier for them to experiment, thus increasing the play motive. Because individuals feel like they uniquely matter in a CFT, they tend to have a higher purpose motive. You can learn more about motivation in Primed to Perform.

- Faster feedback loops: When everyone needed to make a decision or solve a problem is right there in the same team, communication is quicker and more direct. You don't have to wait for information to travel up and down different functional silos. This speeds up learning and execution.

- Reduced context loss: In traditional handoffs between departments (like Product defining requirements and then "throwing it over the wall" to Engineering), a lot of crucial context can get lost. In a CFT, everyone shares the same context because they're involved in the entire process, from understanding the customer problem to delivering the solution.

- Easier prioritization: With a clear mission or problem to solve, CFTs can often prioritize their work more effectively without getting bogged down in competing functional agendas. They have a shared goal that helps them decide what's most important.

By bringing diverse skills together and empowering these smaller units, CFTs aim to foster a stronger sense of ownership and individual contribution. When you're a critical part of a small team with a clear mission, you're less likely to feel like just one more person pulling on a rope. This can significantly boost motivation and, as a result, performance.

However, as promising as this sounds, simply drawing new boxes on the org chart isn't enough. The real challenge lies in the underlying system...

How CFTs need to work to perform at their best

Making Cross Functional Teams truly effective isn't just about putting people from different departments together; it's about fundamentally changing how they work together. The most successful CFTs operate as integrated units that collectively engage in the full cycle of figuring things out and getting things done.

We use the VEGA loops framework to describe this process. It outlines the three learning loops needed to perform adaptively.

Loop 1: The creative, or "figuring it out," loop is where organizations and teams set direction. It involves two steps:

- Visioning: Deciding what problems are most important to solve.

- Exploring: Figuring out how to solve them.

Visioning is collaborative. It requires surfacing together. Exploring is individual. It requires diving alone.

Loop 2: When these two steps result in a direction, companies need to shift to the execution, or "getting it done" loop. This loop also has two steps:

- Galvanizing: Getting ready to execute (resources, structure, process).

- Achieving: Executing and adapting to make progress.

Galvanizing is also surfacing as a team and collective in nature. Achieving is diving, and individual in nature.

Loop 3: Once we've achieved and have a read from the market, we start again with visioning.

The critical distinction for high-performing CFTs is that they don't treat this like a mini-waterfall. You often see teams organized into CFTs "in name only," where Product still does the initial Visioning and Exploring in isolation, and then "hands off" the requirements to Engineering, who are primarily involved only in the Achieving phase. Engineers don't participate in the early problem-solving, designers aren't involved in the final implementation details, and so on.

In contrast, the best Cross Functional Teams ensure that the entire team is brought along and participates in all four steps. Even if certain team members might lead specific phases – perhaps a Product Manager leads Visioning and Exploring, and an Engineering Lead leads Galvanizing and Achieving – the whole team is actively involved throughout. They share context, contribute diverse perspectives to problem-solving, and build collective ownership from idea to execution.

This shared journey through the VEGA loops is what builds collective understanding, accelerates learning, and strengthens feedback loops within the team. It prevents silos from forming within the CFT and ensures that everyone feels a sense of ownership and accountability for the final outcome, not just their piece of the puzzle.

When CFTs truly embrace this integrated, loop-based way of working, they unlock their full potential for speed, innovation, and impact. However, achieving this requires addressing several systemic challenges.

The fundamental problem when designing Cross-Functional Teams

While the promise of Cross Functional Teams is compelling, simply rearranging people into CFTs doesn't automatically lead to the high-performing, adaptive teams you envision. In fact, without addressing the underlying organizational "operating system," this structure can often expose or even exacerbate existing problems.

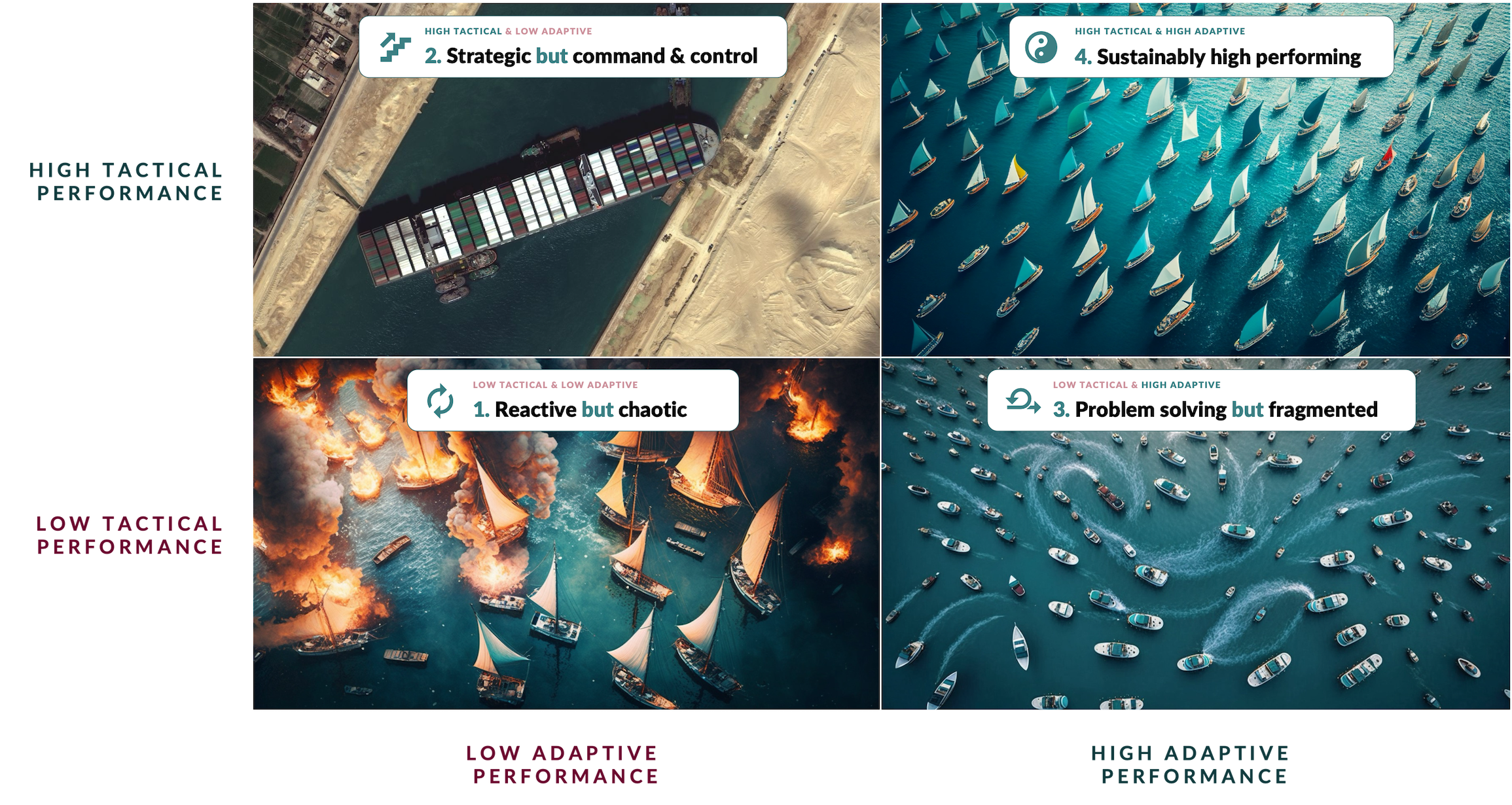

To understand why, it helps to look at organizational performance through two distinct lenses: Tactical and Adaptive performance. Think of it using the boats metaphor:

- Tactical performance is about efficiency and following established plans – like a massive cargo ship staying precisely on course. It's about convergence and creating economies of scale.

- Adaptive performance is about learning, innovating, and figuring things out in the face of uncertainty – like a fleet of nimble yachts navigating unpredictable waters. It's about divergence and creating innovation.

Both are essential for long-term success, but they are fundamentally opposite. Over-emphasizing one can easily undermine the other.

The challenge is that while CFTs are naturally better suited for driving adaptive performance, they may struggle with tactical performance. This can cause CFTs to seek "local optima" at the expense of "global optima."

Drifting to high-adaptive but low-tactical performance.

Imagine an organization that aims to develop an integrated ecosystem, reuse components, enforce common standards, or implement cross-functional strategies. For example, Apple works to make sure that Apple Watches, iPods, Macs, and iPhones are integrated and synergistic with each other.

Without strong strategic alignment mechanisms (like Strategy Checks) that effectively integrate both bottom-up and top-down initiatives, CFT-based organizations can often lose the tactical performance required to pull off this kind of magical synergy.

Falling into low-tactical, low-adaptive

CFTs generally require higher levels of problem solving and influence skills at lower levels in the organization. Many organizations don't have the skill for CFTs to run effectively without better strategy and problem solving processes.

CFTs also benefit greatly from tight customer feedback loops. In B2C companies, CFTs generally perform better because teams have access to customers directly and might be customers themselves.

However, in B2B companies, if the team is distant from the customer, CFTs will be less effective. Again, better strategy, problem solving, and coaching routines will be needed to resolve this gap. These teams are CFTs in name only. They tend to operate as many small waterfalls rather than teams that coordinate and problem-solve together.

The structure of CFTs alone doesn't solve these underlying systemic issues; it often just makes them more visible. The real work lies in changing the organizational operating system to enable teams to thrive in the desired high-adaptive state while maintaining necessary tactical performance.

The six choices you need to get right when setting up CFTs

While the vision of empowered, Cross Functional Teams operating seamlessly through learning loops is compelling, the reality of implementing this structure in a complex organization often reveals deep-seated systemic challenges. Simply rearranging the boxes on the org chart doesn't automatically change the underlying "operating system" – the rhythms, routines, and management practices that govern how work actually gets done.

Here are some critical areas where CFTs often get stuck, requiring deliberate attention and systemic change:

Choose the right level for permanent teaming

Often organizations try to create quasi-permanent teams at the working team level (of 5 to 12 people). In practice, this is usually a problem because that team may not have enough high-value scope compared to a neighboring team who may have too much high-value scope. Moreover, often organizations do not have enough people to fully field these teams. Instead, often the better answer usually is create stable Cross Functional Teams one level above working teams (so like groups of ~50). This gives leaders room to adjust scope, cover talent losses, and create variety while still having small Cross Functional Teams.

Establish clear CFT leadership processes

Leading a Cross Functional Team can be awkward because there is no formal authority. Team members may report to different functional managers outside the CFT. This means CFT leaders have to lead by influence and motivation rather than direct authority, which is very difficult.

Instead, to make it easier for CFT leaders to actually lead their teams, run structured and formal four-monthly cadences. Reach out to us and we'll show you how to use AI to run all three of these cadences incredibly effectively:

- Strategy Checks — Where teams set their strategies, laddering off of the organization's strategies.

- Habit Checks — Where the team works together to improve their ways of working.

- Skill Checks — Where reporting line leaders have a chance to figure out how to apprentice their direct reports who may be on different teams.

Additionally, run prescribed weekly cadences. These include:

- Three standing prioritization and problem solving meetings.

- Weekly written reflections by priority owners.

Redesign reporting line leader roles

In a matrixed environment, functional managers still play a crucial role in developing talent, maintaining technical standards, and ensuring quality. This raises key questions:

- Where does prioritization truly live, especially when functional goals (like technical debt) might conflict with CFT goals?

- Where do technical standards and quality assurance reside and how are they enforced across autonomous CFTs?

- How does performance management work effectively when reporting line leaders have decreased day-to-day visibility into an individual's contributions within a CFT?

- And how is feedback and recognition handled consistently and effectively across both the CFT context and the formal reporting line?

Generally, to make CFTs work at scale, functional reporting lines should be used for apprenticeship, standard setting, and figuring out how to integrate functional goals with CFT goals. Moreover, functions will likely need their own Strategy Checks so they can reconcile their priorities with CFT priorities.

This issue is often a bigger deal than companies realize because the c-suite leaders of these functions are often expected to have their own goals and agendas. When there is no mechanism to reconcile these top-down functional goals with CFT-level goals, tension will ensue.

Maybe CFTs aren't the best choice.

Reorganizing into CFTs isn't universally welcomed.

For example, in one organization that tried to implement CFTs, the engineering team resisted for a few reasonable reasons:

- They didn't feel equipped to problem-solve user problems, so felt like CFT meetings were a performative waste of time.

- They preferred working on a large variety of engineering tasks.

- They wanted to work much more closely with their reporting line leaders for effective apprenticeship, work allocation, and friendship.

Generally, if the combined organization is fewer than 50 people, and if teams aren't set up for success to solve problems in a decentralized way, CFTs may not be a good choice for you.

Problem solving norms

Experiments demonstrate that groups of experts without effective problem solving norms perform worse than non-experts with effective problem solving norms.

For CFTs to be maximally impactful (and minimally dysfunctional), it helps to establish clear ways to solve problems. This includes weekly meetings, written weekly reflections, transparent information sharing, and common problem solving skills.

Adjust performance management

Traditional performance management approaches often become harder for reporting line leaders when their team members are embedded in CFTs. Leaders have decreased day-to-day visibility into an individual's contributions within the CFT, making it challenging to assess performance accurately using legacy methods.

Besides, if functional leaders also have their own priorities AND they are the ones evaluating their subordinates, colleagues in CFTs will not behave as true teammates.

Workplan to go from A traditional org structure to Cross Functional Teams

Implementing Cross Functional Teams effectively requires more than just redrawing the organizational chart. It demands a deliberate, phased approach to evolve the underlying operating system and address the systemic challenges we've discussed. Here is a potential workplan, broken down into key milestones:

Getting the organization excited

- Conduct 3-hour "Introduction to performance and motivation" sessions with the whole organization to build excitement for Cross Functional Teams.

- Share this article with all senior leaders to review to understand what the requirements will be for success.

Diagnosing the current operating system

- Map existing organizational cadences (annual, quarterly, monthly, weekly) to understand the current rhythms of work across all the participants of future CFTs.

- Determine how control functions will participate in CFTs.

- Determine if there are critical holdouts that cannot play roles in CFTs. (For example, in one company, Design prefers to operate outside of the CFT structure. In another platform engineering sat outside of CFTs).

- Assess current strategy setting, and decision-making processes and identify common bottlenecks or escalation paths.

- Evaluate existing resource allocation methods and identify potential conflicts or inefficiencies.

Designing the new operating system

- Determine the optimal altitude for stable CFTs based on organizational needs, talent availability, and roadmap stability.

- Map out the CFTs on paper (what are the CFTs, their leadership, members).

- Define clear leadership roles within the CFT context, separate from reporting lines.

- Determine how CFTs can close their feedback loops.

- Clarify the crucial roles and responsibilities of reporting line leaders in a matrixed environment (talent development, standards, etc.).

- Design strategic alignment mechanisms (like structured Strategy Checks) to ensure cross-CFT and top-down/bottom-up alignment.

- Develop clear norms and processes for effective problem-solving and cross-functional collaboration within and across CFTs.

- Adapt performance management and feedback approaches to fit the CFT structure and emphasize team-based outcomes and adaptive performance.

Implementing new rhythms and routines

- Communicate informally the teaming changes to all critical leaders and experts.

- Conduct workshops to explain role expectation changes.

- Conduct workshops for CFT leaders to set up their kick-offs and routines.

- Cascade communication from leaders to all colleagues including the teams they will work in.

- RAPIDLY, conduct CFT kickoffs designed to get the team deeply excited about the possibilities of their work.

- Provide targeted training and coaching for CFT leaders and team members on new ways of working, collaboration tools, and problem-solving skills.

- Roll out new organizational cadences (e.g., Strategy Checks, Habit Checks, Skill Checks).

- Implement technology and tools that support the new processes and facilitate knowledge sharing and transparency.

Sustaining the change and continuous improvement

- Establish ongoing coaching and support for leaders and teams as they navigate the new operating system.

- Regularly review and refine the new cadences and processes based on feedback and observed effectiveness.

- Measure the impact of the changes on key performance indicators (e.g., speed, innovation, alignment, employee engagement).

- Review current performance management practices and how they align (or don't) with collaborative, adaptive work.

- Gather feedback from employees and leaders on current ways of working, pain points, and desired changes.

Conclusion

Moving to Cross Functional Teams holds significant promise for increasing agility, innovation, and speed. However, as many organizations discover, the structure itself is not a silver bullet. The fundamental challenge lies not in the organizational chart, but in the underlying "operating system" – the rhythms, routines, and management practices that govern how work actually gets done.

True effectiveness in a CFT model requires addressing systemic issues like balancing tactical and adaptive performance, ensuring clear decision-making and accountability, fostering robust cross-functional collaboration, and adapting leadership roles. By focusing on improving the feedback loops and rhythms of work, organizations can build teams that are not only autonomous but also deeply aligned and capable of sustained high performance. Tools like Factor.AI can play a vital role in making these systemic issues visible and supporting the implementation of the necessary changes to the management system, helping organizations achieve both scale and adaptability.